What is a georegistry, and why does it matter?

A georegistry consolidates the basic information scattered across different hierarchies, facility lists, and databases into a single, validated master list. Health facility names, types, GPS coordinates, operating status, catchment areas, and administrative affiliations — all harmonized into one reference that every system can point to.

The impact is structural. When national health information systems, logistics platforms, disease surveillance tools, and campaign planning applications all reference the same georegistry, cross-analysis becomes possible. Without it, master facility lists gradually diverge across databases, coordinates go stale, and the data that should inform billion-dollar health investments becomes unreliable.

In practice, countries like DRC, Niger, Cameroon, and Burkina Faso have learned this firsthand. In the DRC, for example, more than 12 different data sources from various projects had to be merged before the share of health facilities with geolocation in the national health information system could increase from 35% to 80%. In Niger, over 1,800 health facility coordinates were collected and reconciled from thousands of local health workers. These aren’t one-off exercises: they’re ongoing processes that demand continuous data flows and validation.

The integration challenge

Georegistries don’t exist in isolation. They sit at the intersection of multiple systems:

- DHIS2 instances that hold routine health data and organizational hierarchies

- Mobile data collection platforms like IASO or KoboToolbox, where field workers submit GPS coordinates and facility surveys

- Satellite and geospatial data catalogs: OpenStreetMap for roads, WorldPop for population distribution, Copernicus for land cover and climate

- Campaign management systems that need up-to-date facility lists to generate micro-plans

- Visualization and analytics tools: Superset, Tableau, Power BI, that turn raw data into maps and dashboards for decision-makers

Each of these systems has its own data format, update cycle, and access method. The georegistry needs to pull from all of them, reconcile differences, push validated updates back out, and do it reliably enough that health workers and ministers alike can trust the results.

This is a data engineering problem. And in low-resource settings where technical capacity is limited and connectivity is unreliable, it requires purpose-built infrastructure.

How OpenHEXA fits in

OpenHEXA is an open-source data integration platform designed for exactly this context. Built to bridge operational health systems with modern data tooling, it provides the pipeline infrastructure that keeps georegistries connected to the broader data ecosystem.

Here’s what that looks like in practice:

- Automated data pipelines extract facility data from DHIS2 instances, merge it with survey results from IASO, enrich it with population estimates from WorldPop and road network data from OpenStreetMap, and push the consolidated output to visualization dashboards — all on a schedule, with logging and error handling built in.

- A workspace model that gives each country or project its own environment with managed connections to databases, file storage, and compute resources. Data teams can write Python or R notebooks in JupyterHub, build reusable pipeline templates, and run complex ETL jobs without managing infrastructure.

- Interoperability by design. OpenHEXA connects natively with DHIS2, IASO, PostgreSQL, and a growing set of connectors.

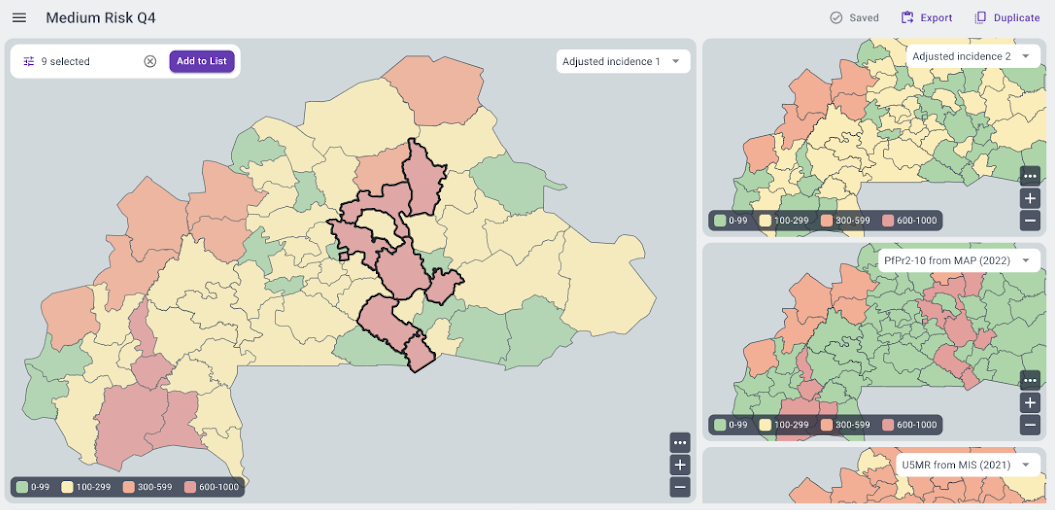

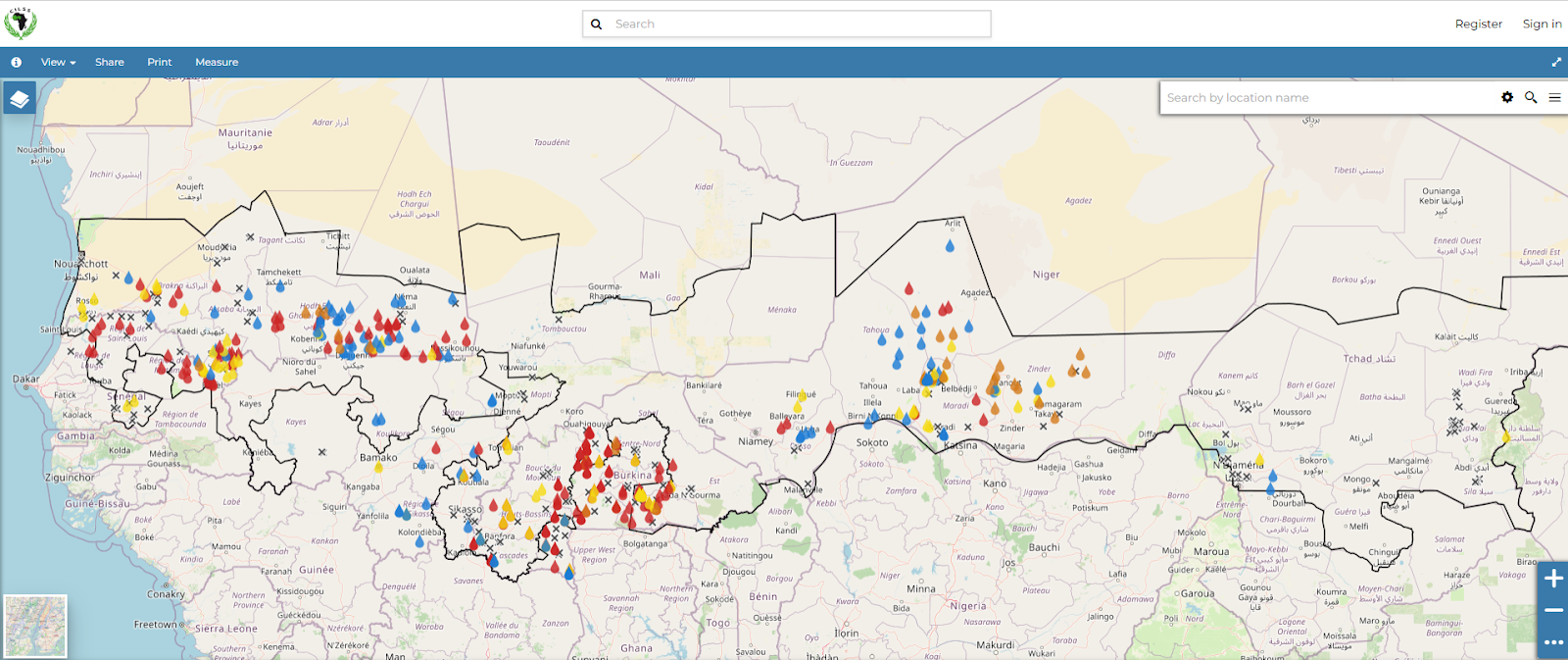

PRAPS interventions dashboard using GeoNode. OpenHEXA data pipelines were applied for complex data workflows

In the DRC, OpenHEXA serves as the primary data integration platform for the Centre d’Opération des Urgences de Santé Publique (COUSP), consolidating surveillance data from multiple DHIS2 instances and other sources for outbreak response. In Cameroon, it powers the data pipelines behind the national health facility map, pulling facility data from DHIS2 and producing the dashboards that health authorities use to allocate resources. For the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, it integrates outbreak and campaign data from 68 countries into a single geospatial data environment.

From ad-hoc mapping to continuous data management

The traditional approach to health facility mapping involves expensive, resource-intensive surveys every few years — surveys that become outdated almost as soon as they’re completed. A more sustainable model treats the georegistry as a living system, continuously updated through routine data collection, field validation, and automated pipelines.

This is where the combination of a georegistry platform like IASO and a data integration platform like OpenHEXA becomes powerful. IASO handles the frontline work: mobile data collection, change request workflows, multi-level validation, and bidirectional sync with DHIS2. OpenHEXA handles the backend: merging datasets, running quality checks, computing accessibility models, generating automated reports, and feeding results back into the systems that health workers use every day.

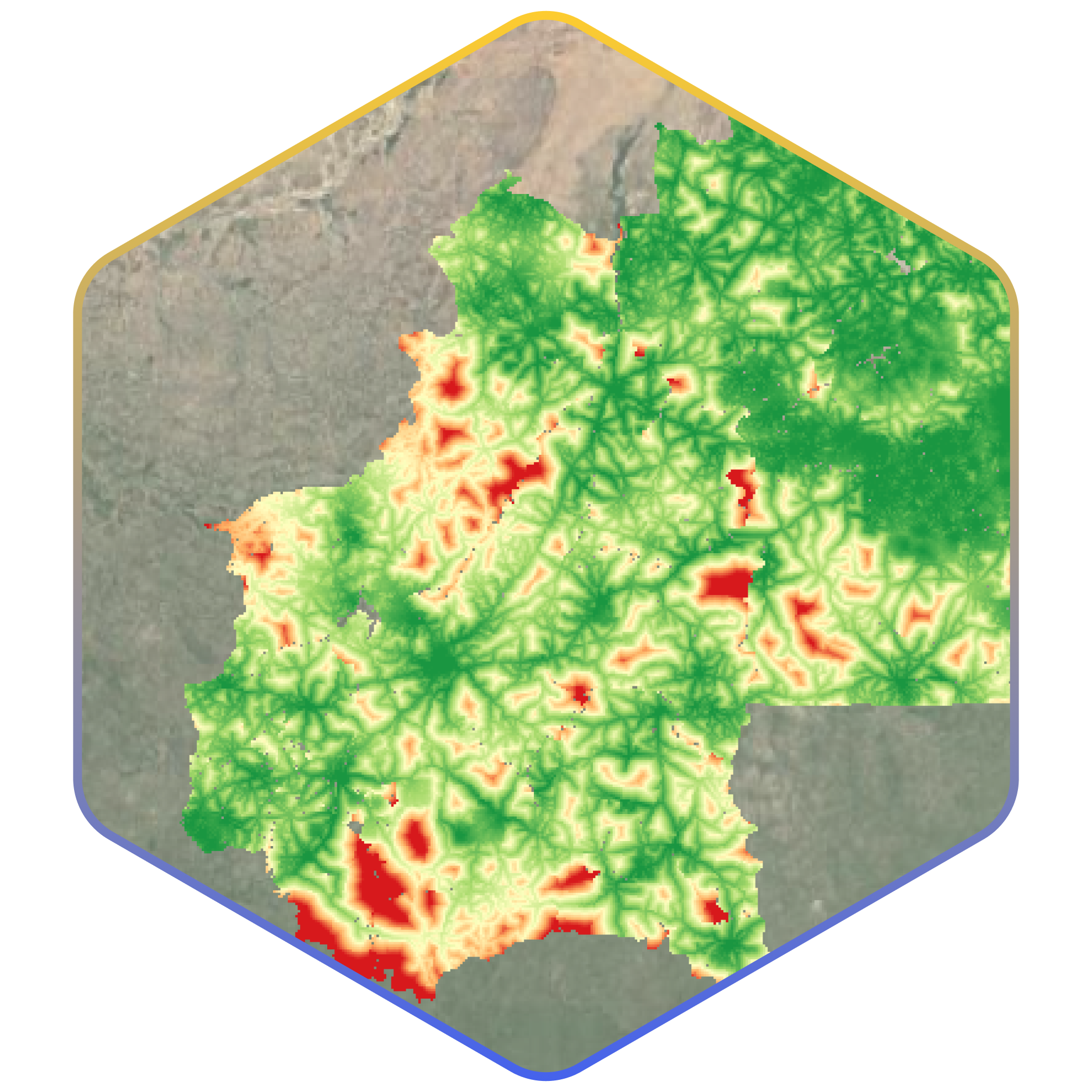

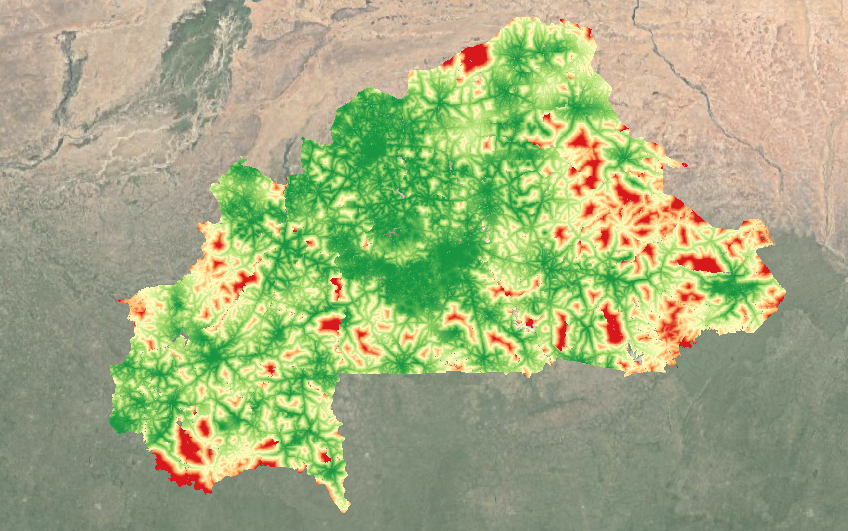

Health service accessibility produced through AccessMod (Burkina Faso). Raster colors represent the time required in minutes to reach the nearest health service provider. The data acquisition and data processing is carried out via OpenHEXA

Each vaccination campaign, each facility survey, each boundary correction becomes an opportunity to improve the georegistry. And because the data flows are automated, the improvements propagate immediately across connected systems.

In Cameroon, this feedback loop has supported over eight health campaigns since 2023, with each campaign building on and refining the geospatial data established by the previous one. In Niger, routine structural data collection at the start of each year now feeds directly into the georegistry through automated pipelines, replacing what used to be ad-hoc, project-driven updates.

The bigger picture: data sovereignty and local ownership

A data integration platform for georegistries is a governance tool. When countries own their data infrastructure, they control how data flows, who validates it, and how it’s used. OpenHEXA supports local hosting (Niger’s Ministry of Health runs its own instance on government servers) and is designed so that national data teams can independently manage and extend their pipelines over time.

This matters because georegistries are inherently political objects. They define which facilities exist on the official record, which communities fall within which catchment areas, and how resources get allocated. The technology that manages this information needs to be transparent, auditable, and under the control of the institutions that are accountable for it.

If you’re working on health facility mapping, master facility list management, or campaign planning in an LMIC context, and you’re dealing with fragmented data across multiple systems, OpenHEXA might be what you need to connect the pieces.

It’s open source, it’s built for the constraints of low-resource health systems, and it’s already running in production across nine countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

For more information: Contact us